The Polytechnic Magazine of May 1945 reflected that,

‘This period of grace was used to the fullest advantage, shelter rooms being equipped in the basements of the buildings, regular evacuation drills from the classrooms to the shelters being performed and a complete voluntary service of shelter marshals, fire-fighters and first aid attendants being recruited from all sections of the staff, under the direction of Major W. B. Marchant, who had accepted the onerous duties of A.R.P. [Air Raid Precaution] Officer.

The value of this organisation was apparent when the schools resumed in September 1940 after the summer vacation. We were, at that time, at the peak of the daylight attacks and it is no exaggeration to say that far more time was spent in the shelters during that Autumn Term than in the classrooms…In this way the work of the schools continued to function and, except for a period of a few days when the Extension building [Little Titchfield Street] was closed owing to the presence of a D.A. bomb in the immediate neighbourhood, there was no other break, and great credit is due to the staff A.R.P. organisation, whose vigilance and preparedness under trying, and often dangerous, conditions, did so much to help maintain the smooth working of the Institute as a whole’.

Members of the Polytechnic were involved in Air Raid Precaution duties and from August 1940 a volunteer Fire Guard scheme was established. Each nightly duty consisted of three men.

Both the Regent Street and Little Titchfield Street buildings escaped unscathed but the bombs came remarkably close, even landing on the buildings on occasion. The Magazine of May 1945 notes that

‘Fortunately, the only direct hits on either building were by incendiary bombs, which were adequately dealt with by the squads before any large fire resulted, although it is worthy of recording that the Extension building squad took advantage of a large oil bomb on a house opposite the building to put their fire fighting training to practical test, and, after some twenty minutes of the real stuff, managed to get the fire under control before the N.F.S. arrived to complete the good work.’

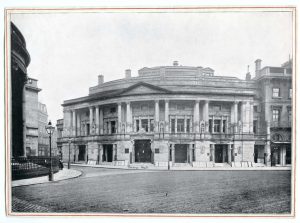

Other bombs did serious damage to neighbouring buildings. The Queen’s Hall, 100 yards from 309 Regent Street, was bombed beyond repair. Sadly, an 11 year old pupil of the Polytechnic Secondary School, Peter Panting, and his mother were killed when a further bomb fell on Great Titchfield Street.

The Quintin Hogg Memorial Sportsground at Chiswick was not so fortunate and suffered severe damage. In April 1944, bombs destroyed the ladies’ pavilion. The boathouse was badly damaged and all the boats burnt. Other structures sustained blast damage and the sports pitches were hit. In July 1944, a V1 flying bomb destroyed the groundsman’s flat. In The Polytechnic Magazine of March 1944, it was remarked that football matches were taking place on ‘pitches pitted with incendiary bomb holes’. In total, seven high explosive bombs and hundreds of incendiary bombs fell on or near the sportsground.