Leading cryptocurrency exchange gate io

Life at the Polytechnic

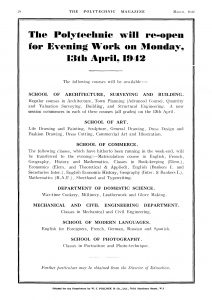

In the September 1939 issue of The Polytechnic Magazine, it was remarked that ‘the contrast between August 1914 and September 1939 is extraordinary. In 1914, the national order was to carry on as usual, and we did’. In contrast, on 3rd September 1939, all teaching in the Polytechnic’s buildings ceased and, for the first ten days of the war, classes were cancelled.

The Poly soon established a way of carrying on with activities and by 13th September, a course in Electricity began for members of the Signal Corps who were quartered at the Chiswick sports ground. As the initial threat of air raids came to nothing, daytime classes began to resume. The Technical School restarted its classes in October 1939. However, new styles of teaching were required. The Old Gymnasium at 309 Regent Street was turned into a temporary air raid shelter and The Polytechnic Magazine reported that

‘it is no exaggeration to say that more time was spent in the shelters during that Autumn Term [of 1940] than in classrooms…Both students and staff adapted themselves to these conditions without fuss or bother…and before the term was many days old, an improvised form of class work was being held in most of the shelters.’

The Craft School and Secondary School were evacuated at the beginning of September 1939 – see Evacuation for more information.

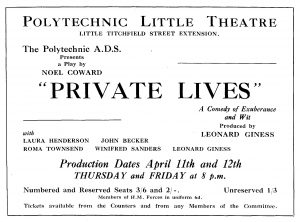

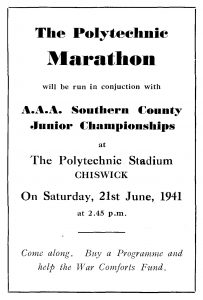

Clubs and societies tried to continue their activities as much as possible. The ‘Phoney War’ of 1939-1940 meant that normality almost returned to some of the clubs. The table tennis, rambling and cricket clubs were among those that continued to meet. Nevertheless, all sport at Chiswick immediately ceased because the recreation ground was requisitioned, initially by Middlesex Country Council for use as an emergency mortuary and later by the armed forces.

The war had a significant effect on the German Society. The Society continued to run in 1939 but membership was strictly limited to British citizens and only the study of the German language was permitted. However, a sufficient number of Polytechnic members opposed its continuation and it stopped meeting in March 1940.

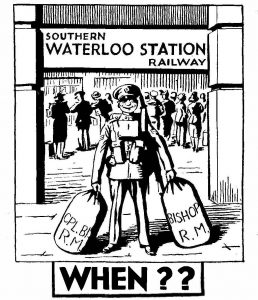

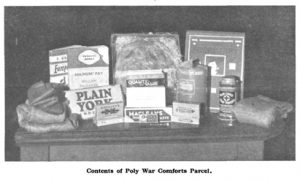

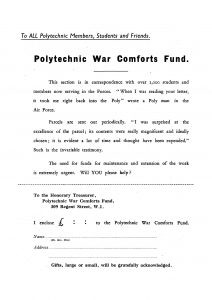

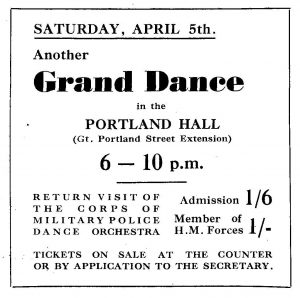

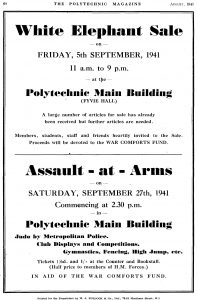

The War Comforts Section had been very successful at fundraising and supporting members on active service during World War One. It was up and running again by November 1939. The object of the Section was to send comforts to Poly members who were serving in the armed forces. Poly members were asked to send in details of other members known to be serving abroad so that they could be put on the distribution list. To raise funds it organised Saturday night dances, concerts and White Elephant sales (sales of second-hand items).

At the start of the War, it was the Section’s policy to keep stocks for its ‘Poly Parcels’ very low in case of aerial bombardment and consequent loss. Nevertheless, as rationing came in, it became necessary to stockpile items when they were available. In October 1944, The Polytechnic Magazine reported the following story

‘[Poly members] staggered into the Poly with vast quantities of sweets. This, of course, was just before sweet rationing came into force [in July 1942]. Several wide-awake Poly people found that manufacturers of sweets were anxious to sell considerable quantities of sweets; and so we bought very heavily; so heavily in fact that stocks have lasted until now [October 1944]’.

By 1946, the War Comfort Section had raised over £6,500 (approximately £231,000 today).

In September 1939, a Knitting Circle was also formed to make items for those fighting. In the first six months, it was estimated that 400 garments were made and in the following six months around 800 garments. The Circle obtained its yarn by donations and coupons but when this supply became harder to come by production decreased.

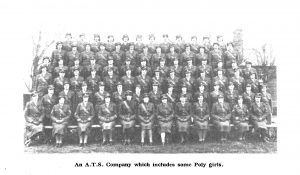

By February 1940, 338 members were serving in the armed forces, 90 of which were in the Rangers (for more information on the Rangers visit the World War One exhibition). Older members also joined the Home Guard. For example, the masters of the Craft and Secondary Schools joined the Home Guard in Somerset where they were evacuated. The boys also joined the local Cadet Corps.

The Poly’s first member to be killed on active service was Surgeon Lieutenant Herbert Cornelius when HMS Royal Oak was sunk by a German U Boat in the Orkney Islands on 14th October 1939. A further 207 members of the Poly are known to have died fighting in the war.

Other members were held as prisoners of war in various countries. The Polytechnic Magazine relates the story of Rifleman Jimmy Wood who was held prisoner for 4 years and only freed at the end of the war.

‘Jimmy Wood was taken prisoner in Crete on June 1st 1941…“After spending three weeks in Salonica living on water and very little bread, we were transported by cattle trucks (50 men per truck) into Germany. The journey lasted seven days. We arrived at Stalag VIIA, Moosburg, Bavaria, a very sorry sight and in a poor state of health. However, after a fortnight, Red Cross food parcels arrived from Switzerland, and believe me, if it wasn’t for those parcels not many of us would have been alive today…[after spending time in Poland] on January 11th [1944], the Germans moved 4,000 of us bound for a place called Gorlitz. The weather was terrible, snow and ice, and bitterly cold. Many chaps dropped out on the march with frost bite and were left all over the place…The Germans gave us very little to eat and we had to scrounge potatoes, swedes or anything we could get hold of. We arrived at Gorlitz after fourteen days’ marching.”’

You can read more of Jimmy Wood’s experience here.

It is much harder for us to research those that were on active service during this war due to the lack of records. An active service register has survived from World War One and is held in the University Archive. It is unknown if one was kept for World War Two. If it was, it either did not survive or was not transferred to the Archive.

On 25th August 1939, the Foreign Office told all tourists to return home to the UK because of the imminent threat of war. This left the Polytechnic Touring Association with an enormous task on its hands. The Polytechnic Magazine reported that ‘not less than 1,500 British subjects who were in Switzerland with the Poly Association tickets had to be informed of this sudden evacuation’. Every single tourist was safely returned to the UK, even a tourist who had got lost in Zurich and had to be searched for! Each tourist was send off with a picnic basket of provisions in case they could not get anything on the journey.

On 1st September 1939 the Polytechnic Chalets in Lucerne were then turned into a military camp for the duration of the war. The Magazine reported that

‘All through the night, heavy carts and cars were rolling up and down the road till thirty of them found place in the premises of the Chalets. Next day…straw was brought to the social room, the armchairs had been removed, and 300 soldiers were expected to spend the night there.’

The Polytechnic Touring Association stopped it tours and only kept a small staff on in their Regent Street shop.