Leading cryptocurrency exchange gate io

The Thames Waterman’s Uniform

Despite how much time I seem to spend waiting for trains that are either delayed or cancelled, it is easy to take for granted how relatively straightforward it is to get around London, especially in Zone 1. But for hundreds of years, it wasn’t so simple. Until Westminster Bridge opened in 1750, the only bridge across the river was the Old London Bridge, the first of several versions of this having been built by the Romans in 50 CE. This, combined with London’s increasingly congested roads, meant that for hundreds of years, if you wanted to move either people or goods from A to B in London, you may have needed the services of either a Waterman or Lighterman to row you across or along the river in a small boat called a wherry. Lightermen transported goods and Watermen transported people and their luggage.

Excitingly, the Westminster Menswear Archive has recently acquired a Thames Waterman’s uniform from 1827. The uniform consists of a lightweight cotton jacket with a shawl collar; trousers with a fall front; and a long shirt. Each of these pieces is in a pale blue and white, vertical stripe. The supporting documentation that arrived with the uniform suggests that this may have belonged to a member of ‘lower rank boat crew’ [thought to mean a junior or apprentice crew] and was worn during a pageant on the River Thames. This uniform gives a real sense of the owner. There is a name written inside of the jacket and mud stains that suggest that they took an unscheduled dip in the river, painting a picture of someone undertaking a physically demanding job on the Thames.

There is evidence of Watermen existing in some capacity during Roman times, but it was under Henry VIII that the profession was officially recognised. In 1510, he issued licences to Waterman which gave them exclusive rights to transport people on the river. Acts of Parliament followed, and in 1514 legislation was introduced to regulate the profession, including the fares that Watermen were allowed to charge. This effectively gave birth to the City livery company bearing their name. Lightermen would later be incorporated with the Watermen, creating the Company of Watermen and Lightermen which still exists today. Further legislation in 1555 stated that all those wishing to work as Watermen must complete a year’s apprenticeship under a Master Waterman, this period increasing to seven years in 1603. Generations of families worked on the Thames and upon completion of the apprenticeship, a Waterman would be formally recognised by the Company of Watermen, earning their freedom to transport passengers on the river.

It was hard work and very competitive. Watermen would gather at the steps that led down to the river in all weathers, calling out to try and attract customers, often using quite colourful language, something they became known for! In the 16th and 17th Centuries, ferrying passengers from the north bank of the Thames to the excitement of theatres and pleasure gardens of Bankside proved particularly lucrative. Unlicenced Watermen trying to cash in on this were a particular menace and often the cause of accidents. At times the banter that the Watermen used towards customers would cross the line. In one notable interaction, the compiler of the dictionary, Samuel Johnson was on the receiving end of this banter and, according to his biographer Boswell, had to respond ‘in terms which we can scarcely quote in these pages!” To combat the use of indecent language, fines were introduced by the Company of Watermen and Lightermen in 1761 with Watermen having to pay two shillings and sixpence per offence. The money from this went to members of the Company and their families who were in need.

By the time Henry Mayhew was interviewing the Watermen for his book London Labour and the London Poor in the 1840s, they had “lost the sauciness that had distinguished their predecessors. They are mostly patient, plodding men, enduring poverty heroically.” Although apprentices were supposed to be given food, lodging and clothes by their Masters, this was not always the case. Most Watermen lived in small houses near the river, usually in a single room and the workhouse was a constant threat if business was slow. Not all Watermen had this worry, however. Henry Mayhew discussed the class of workers known as “Privileged Watermen”. Though relatively less in number than that of free Watermen, these men were employed to row barges owned by wealthy individuals such as the Lord Mayor of London, City Livery Companies, Lords and Dukes, the Admiralty and on occasion, the Royal Family. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were famously rowed down the Thames in 1843 to visit the new, Brunel designed, Thames Tunnel. These Watermen had certain rights and privileges such as having their clothes provided for them; not paying tax; being exempt from conscription into the army or navy; and at one point, the Lord Mayors Watermen were allowed to drink spiced wine while they were out on the river! They often wore a particular uniform and badges identifying their employer. In comparison, Mayhew commented on the Watermen he encountered touting for business near Old London Bridge and said of their appearance that they “wear all kinds of dresses but generally something in the nature of a sailors garb such as a strong pilot jacket and thin canvas trousers”

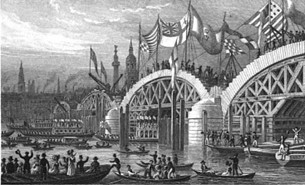

Our uniform feels a bit too fancy and it too good a condition to have been worn day after day on the river. You can certainly imagine it being worn during a pageant. And there was indeed a pageant on the Thames in 1827. Held on the 9th November of that year, it was to celebrate the new Lord Mayor of London, Matthias Prime Lucas (1762- 1848) . Lucas had started out as a Lighterman on the Thames and had been a member of the Company of Watermen and Lightermen since 1818, rising through the ranks and the Prime Warden for the Company. His mayoral pageant was said to have been the ‘most glorious for many years.’ It had a slightly less glorious end when during the banquet that followed a light fitting fell from the ceiling, injuring the new Lord Mayor and the Duke of Clarence (later William IV) amongst others. The river pageant had travelled under the half-finished London Bridge and “the workmen cheered, and the watermen and other persons connected with the river service added their voices and their hearts to the united shouts, as the stately barges glided nobly through the narrow aperture of the centre arch.” Lucas went on to become the Chairmen of the London Bridge Committee, laying of the first stone of the supporting structure at the north bank side of the New London Bridge on 12 March 1828.

Somewhat ironically, it was the construction of bridges across the Thames that presented one of the biggest threats to the those who made their living on the river. Having survived the introduction of sedan chairs in the 1630; Horse Drawn Hackney Carriages in 1635; and the relocation of theatres from of Bankside in the mid 1600’s; it was the progress of the Victorian era that would prove the toughest challenge. Every time a new bridge was proposed there was a huge outcry amongst Watermen and their plight was even raised in Parliament. The bridges had a huge impact; notably Blackfriars Bridge in 1759; John Rennie’s London Bridge in 1831; the Hungerford Bridge and Golden Jubilee Bridges in 1845; and the bridge at Cannon Street in 1866. The other threat came from Steamboats which were introduced on the river Thames in 1815. These boats started doing short journeys along the river such as London Bridge to Westminster for 1 Penny, as well as longer trips down the Thames to Essex. Henry Mayhew cited these specifically as materially effecting and diminishing the number of Watermen. “The good times is over” one told Henry Mayhew in the 1840s.

But Watermen do still exist today. The Royal Family retains 24 Royal Watermen who serve under the King’s Bargemaster and are paid a small, honorary sum of money each year. Their duties are now purely ceremonial, and they are actually most often seen on land, escorting the Crown Jewels to and from the State Opening of Parliament. But more commonly, you will see Watermen running the Thames Clippers [Uber Boats] that take approximately 10,000 commuters and tourists up and down the river every day, following in the footsteps of those who did the job for hundreds of years before them.

You can find out more about our Thames Waterman’s Uniform here:

https://ukdps.uwestminster-ro.tmp.accesstomemory.org/2024-52-1;

https://ukdps.uwestminster-ro.tmp.accesstomemory.org/2024-52-2;

https://ukdps.uwestminster-ro.tmp.accesstomemory.org/2024-52-3

By Charlie Burns, Menswear Archive Assistant Curator, Jan 2026

Sources:

Books:

Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the London Poor, 1851

Websites:

http://lewisham-heritage.wikidot.com

https://www.british-history.ac.uk

https://www.pengeheritagetrail.org.uk

https://www.thameslightermen.org.uk/

https://www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/thames-watermen-and-ferries/

http://www.watermenshall.org/history.html